There’s an old saying that “Money decreases if you count it too often.”

It’s usually said half-jokingly, but as I’ll show you, there’s more truth to it than you might expect. Modern investing psychology and probability theory back this up.

So, if you’ve ever:

- Sold a stock only to watch it rise afterwards…

- Checked your portfolio again and again during the day…

- Felt more pain on red days than joy on green days…

…then this is for you.

Let’s imagine you own shares of Microsoft (MSFT). This is a rock-solid business; everyone knows it’s reliable and grows about 15% every year. We’re going to assume a few numbers to make the math easier.

Here’s the twist:

- Each trading day, the stock either goes up by +1% or down by −1%.

- There are about 250 trading days in a year.

The question: How many “up” days do we need to end the year with a 15% gain?

The math says 133 positive days. That’s just 53.2% of all days. In other words, we only need 133 out of the 250 days to end up with 15% gains by the end of the year.

This is the power of small advantages, repeated many times. Provided one can perform the same experiment repeatedly, even if the odds are barely in one’s favor, the end result can be massive.

The ‘repeatedly’ part is important. If you have a 53% win rate for a stock that either goes up 1% daily or down 1% daily, your probability of NOT losing money is over 84%! This is just one example of how a small advantage in the market can be used to generate BIG returns.

You must be wondering now, if the math checks out and the markets are really that simple, why is it so hard to actually make money? The answer also lies in math, though in a slightly different branch.

This brings us to a concept called ‘Entropy’. Nothing to worry, we’ll break it down for you. We first define the terms ‘signal’ and ‘noise’.

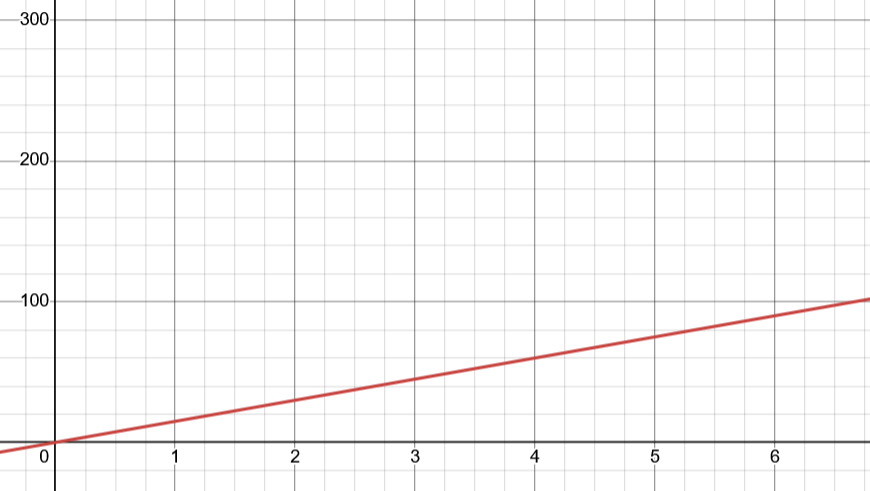

Signal

A ‘signal’ is the ultimate truth. In our case, the signal is the fact that MSFT makes the best software, it dominates the market, is efficient, and returns 15% every year.

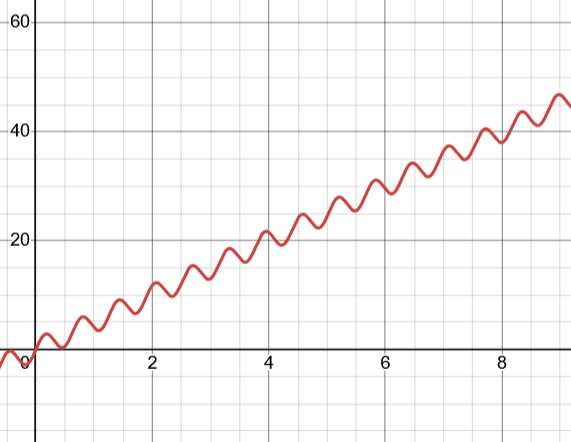

The following graph shows how the business performance for such a stock should look like. A straight line.

When we are looking for the next investing idea, we are basically searching for signals like this. We go through financial statements, management profiles, business models, etc, just to look for the right ‘signal’.

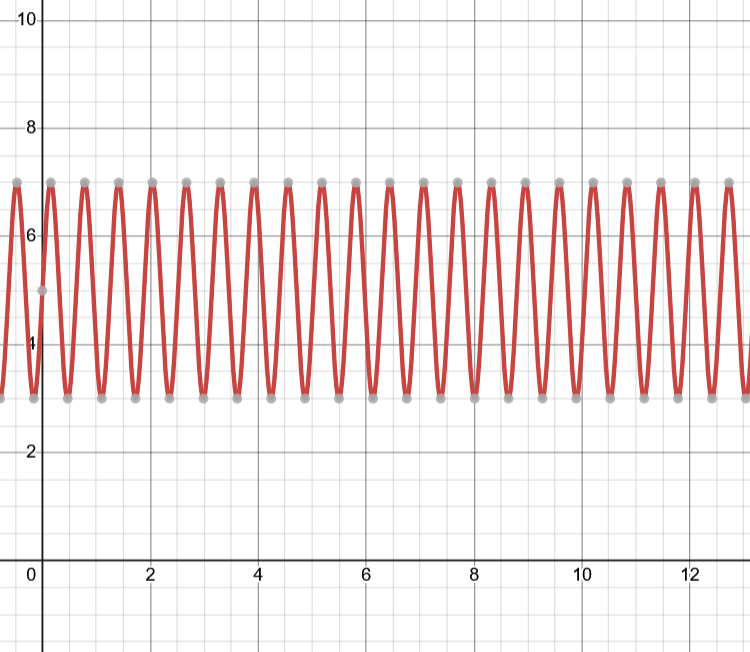

Noise

Our quest for searching the perfect ‘signal’ is made hard by ‘noise’. Noise is any data, news, opinion, or event that distracts you from trusting your signal. It could be a mutual fund selling MSFT, a competitor showing up, a tech virus, or simply market rumours.

It adds no value, but does everything to distort the original signal. It adds randomness to the signal, which in turn makes it hard to read the signal. In simple words, when we look at a perfectly fine business, we have to deal with a lot of noise that messes up our true judgment of the business.

If you combine the business growth with the market noise, you get something like the attached graph. Notice how it resembles the stock price of a business. Randomly going up and down, but eventually getting to its destination. Market noise only causes temporary disturbance.

Entropy

This is where Entropy comes in. Entropy is the ‘confusion’ that noise (market rumour) generates in the business(stock) we are analyzing.

Now imagine if we were checking the stock price of MSFT every single day. Some days it would be up 1%, some days it would be down 1%.

Both of these are measurements of noise. On any given day, there is a 53% chance that we will have made money on the stock(whether we made money today or tomorrow is irrelevant).

Compare this to someone who only checks the stock price once a year. We already established he has an 84% chance of not losing money. This is a significant improvement on the 53% for the person who checked the price daily. The reason for this big difference is Entropy.

The once-a-year portfolio checker has absolutely no noise to deal with. He isn’t confused by the daily stock movement. He just bags his 15% return at the end of the year.

This is one reason why dead people’s portfolios outperform the market. They have no entropy. They get all the returns that the business makes, which is what the purpose of investing is to begin with.

In any engineering system, you need to develop additional systems to reduce noise. In investing, all you need is to close your eyes(assuming the signal is reliable, of course).

In reality, we need to strike a balance; we can’t just close our eyes to all noise.

This is why quarterly financial results exist. They strike the right balance for any business to measure its own success, without being confused by noise or the unpredictable ups and downs in the course of business. For investors, analyzing the financial results every three months is therefore enough. Everything else is noise.

Mathematically, it doesn’t make any sense for a long-term investor to check stock prices daily. It is a futile exercise and can only lead to wrong decisions.

There is also the psychological aspect. Stock prices dictate our mood, and therefore, our decision-making. An investor will react differently to a +1% day than to a -1% day. Loss aversion tells us that a loss of 1% hurts much more than a gain of 1%.

To determine how this affects an investor’s portfolio, let’s put numbers to this.

Suppose we assign:

- +1 unit of happiness for a positive day

- -2 units of happiness for a negative day.

An investor who checks the portfolio at the end of the year gets their 15% return and takes the +1 unit of happiness.

An investor who checks his portfolio every day can either gain a unit of happiness or lose 2 units of happiness daily. By the end of the year, this investor will still make 15%, but end up with -101 units of happiness(133 – 2×117).

Clearly, the more eager investor is worse off. He is less happy. But that’s not the worst part. In his pursuit of more happiness, this investor starts taking on more risk. He then goes down a rabbit hole he can never recover from.

This has been observed in various studies. The buy-and-hold investor wins(especially in trending markets) while the one modifying his portfolio too often loses. So these are not just theoretical concepts. They are the mathematical answers to what has been observed in the stock market for years. The smart ones do not fight what has already been established. Fortune may ‘favor’ the brave, but it consistently rewards the disciplined.